The art market has been extremely dynamic for many years, even the pandemic could not break this dynamic, auction houses are recording record sales. More and more new target groups are finding their way to art, be it through new distribution channels or through extraordinary events.

Unfortunately, this boom also has its dark side. Where there is a lot of money at stake, the demimonde is also easy to find.

Headlines such as the one about Inigo Philbrick, a London art dealer who obtained over $86 million through various fraudulent practices, or Wolfgang Beltracchi – also dubbed the German master forger, prove what insiders are already familiar with: the art market is certainly not only made up of philanthropic gentlemen talking in the finest Oxford English about current trends and the art-historical significance of the avant-garde – there are plenty of black sheep!

The case surrounding New York’s oldest art gallery Knoedler reveals that even seemingly established institutions need to be critically reflected upon and that even the former chairman of the world’s top-selling auction house – Dominico De Sole – privately fell for an art forgery. The publication of the Knoedler scandal, in which more than $80 million worth of fake artworks were sold, has now also drawn the attention of the mass media to the non-transparent market mechanisms and brought the Netflix documentary “Made you look” to light.

However, the problems mentioned are not only to be found in the field of “blue chip art”. Hubertus Butin – expert in the field of art forgeries and art historical assistant to Gerhard Richter – describes in his book “Kunstfälschungen – Das betrügliche Objekt der Begierde” (Art Forgeries – The Fraudulent Object of Desire) that an estimated 50 per cent of the art prints on the market are forgeries and that most forgeries occur in the low thousands, as auction houses, galleries and collectors do not look that closely here. How do the authorities react to this state of affairs? Auction houses are usually not liable, art dealers themselves have been deceived and the forgers themselves produce abroad.

But how can private individuals continue to enjoy art and participate in this exciting market without falling for forgeries or even promoting them? The Keil Collection Heidelberg has spoken to experts from various areas of the art market and they all agree on one point:

Ask, research, keep calm and ask again!

Before buying any art, the seller should be asked in detail about the so-called provenance of the work. How and when did it come into his possession? Has it already been presented to experts? What should be done if it subsequently turns out to be a forgery? A renowned Berlin art dealer has given the Keil Collection some important advice: “Hands off time-critical offers à la the estate has to be sold in the next few days – we don’t have time to examine the works. People who have an interest in the honest sale of their art will also be able to be patient for a few days”.

And what does this have to do with Peter Robert Keil?

Well – a large number of paintings and other objects by PETER ROBERT KEIL, whom we hold in high esteem, can also be found on the internet. And the inclined collector has been asking himself or herself for a long time:

- Could Peter Robert Keil have created all this himself?

- How can the overly clear differences in quality be explained?

- What about the credibility of alleged provenance documents?

A little research quickly shows that the utmost caution is also called for with regard to Peter Robert Keil. Many of the works seem to be of rather dubious provenance.

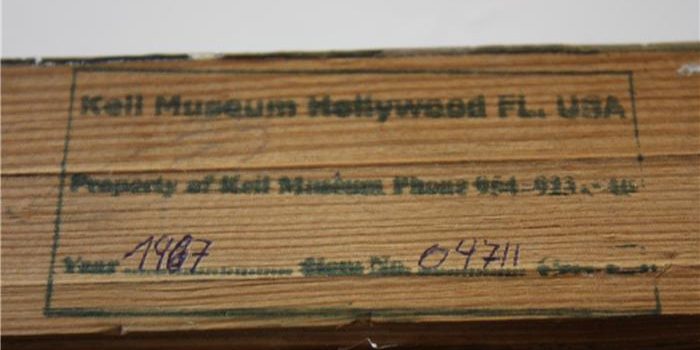

- What does the stamp of a “Keil Museum” in Florida prove if this museum does not exist?

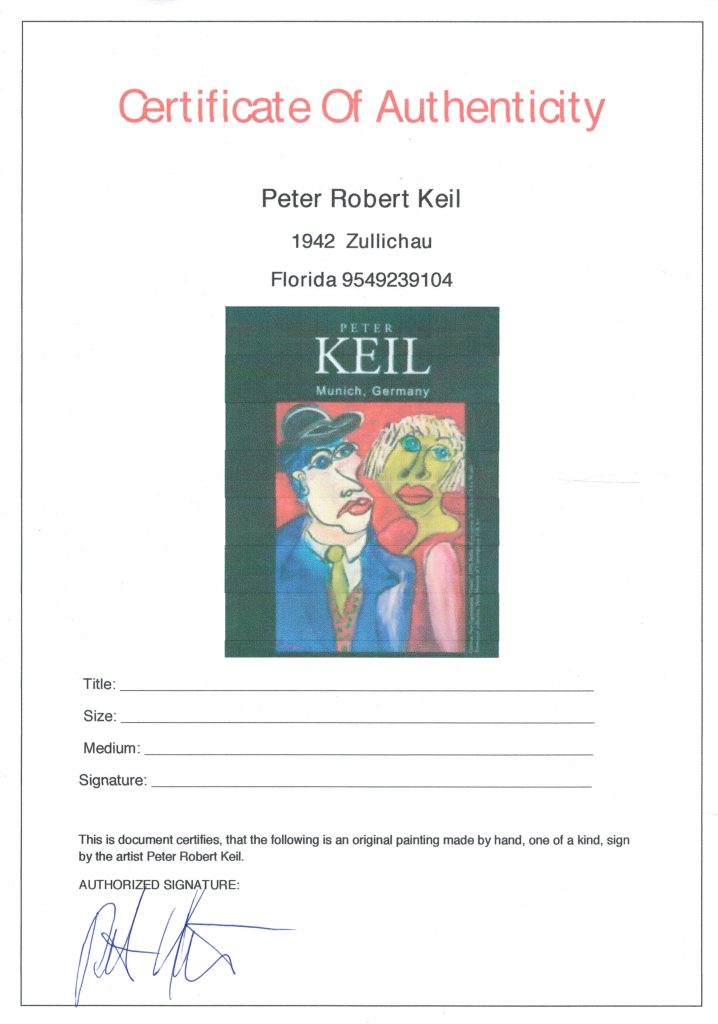

- What does a blank certificate mean if it does not refer to a specific image?

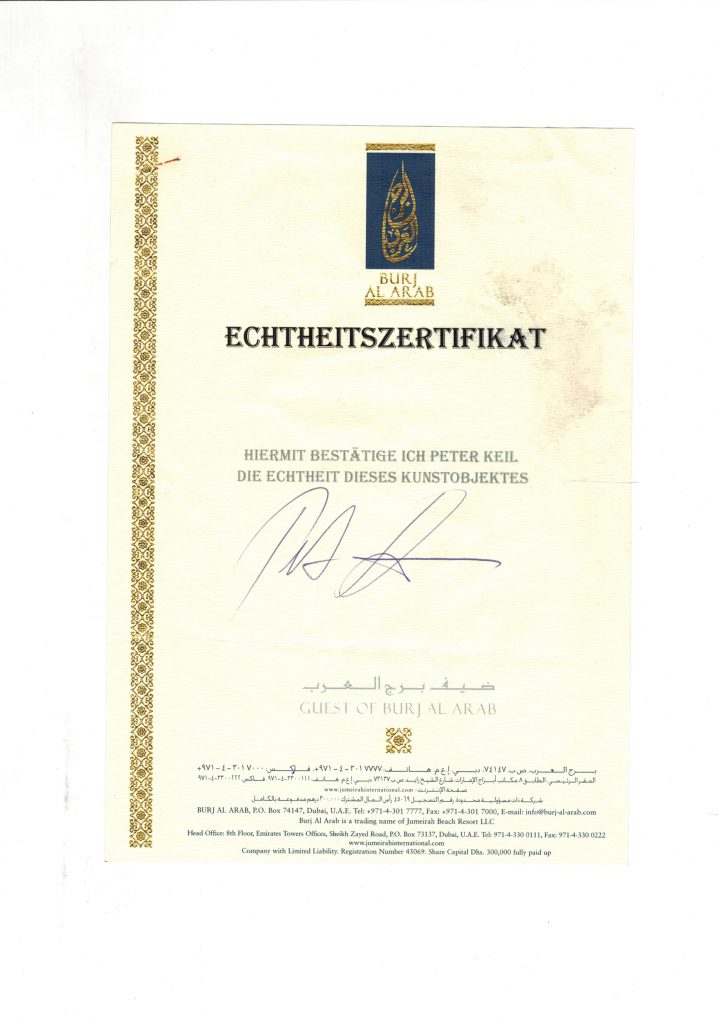

- And how serious is a certificate on the stationery of a well-known hotel in Dubai? Isn’t its aristocratic appearance supposed to convey nobility where caution would be appropriate?

And if the documents are already so dubious, what about the works that are supposed to be legitimised by them? It is hardly to be assumed that a genuine Peter Robert Keil has to be documented with a fictitious museum stamp, and doesn’t a confirmation on hotel stationery immediately nourish doubts about the authenticity of the work “certified” on it?

In order to finally bring light into the darkness here, the Keil Collection Heidelberg has set up a Zertifizierungsprozess since 2014 that follows very strict rules. A four-eye principle – Peter Robert Keil and the art historian Dr. Hoge – examine the respective work under the most diverse aspects and thus form an opinion about the authenticity of the work.

In the meantime, more than 20 certification dates have taken place, during which more than 7000 works have been certified. There is a first volume of the works directory, the second volume is planned for 2023.

Because not everywhere that says Peter Keil on it is also PETER ROBERT Keil in it!